Detecting Reproductive Events

Normally researchers would look for pups or young to know if an animal has given birth. However, in Steller sea lions that have pups in remote places, scientists may not always see them, especially if the females go somewhere different or die. The 2nd generation of the Life History Transmitter (LHX2) that was developed and being used by 2014, uses the animal’s internal body temperature to determine when a young female becomes reproductively mature and also to detect actual birth events.

Surprisingly, scientists do not know for certain at what age Steller sea lion females have their first pup, whether they have one every year after that, and how many pups they have over a lifetime. In studying the population ecology of Steller sea lions, the overall numbers of births that happen each year are important. There is some speculation that Western Steller sea lions may be experiencing low birth rates possibly due to pollution or lack of food. Low birth rates can lead to the decline of an otherwise healthy population.

Surprisingly, scientists do not know for certain at what age Steller sea lion females have their first pup, whether they have one every year after that, and how many pups they have over a lifetime. In studying the population ecology of Steller sea lions, the overall numbers of births that happen each year are important. There is some speculation that Western Steller sea lions may be experiencing low birth rates possibly due to pollution or lack of food. Low birth rates can lead to the decline of an otherwise healthy population.

For the Steller sea lion, as in many wild animals, most of the young born do not survive to be old enough to reproduce and have pups of their own. In order to maintain a stable population size, each female that survives to be old enough to reproduce needs to have many pups over her lifetime. Just how many pups depends, in part, on how many females survive long enough to breed. This is why it is important to know how long Steller sea lions are surviving, why they are dying and how many pups each female will have.

How does the body temperature indicate if a female Steller sea lion has given birth?

Most mammals, including humans, undergo hormonal changes that occur during pregnancy and birth. Hormones also affect body temperature. These changes should cause a temperature rise that the LHX2 tag can detect.

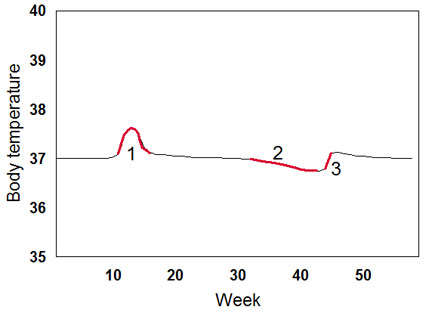

Scientists have discovered that it is possible to detect these temperature changes from research in sea otters. The image below is an approximation of the body temperature in a female sea otter over the course of one year.

Event 1 is a temporary rise in temperature associated with the female becoming ready to mate, called ovulation. Event 2 is a continuous decline in temperature during late pregnancy. Event 3 is a very abrupt and pronounced jump in temperature associated with birth. This image was prepared from data kindly provided by Dr. Tim Tinker, from the Santa Cruz Field Office of the U.S. Geological Survey.